When I listen to the recitations of the late Sheikh Noreen Mohammed Siddiq, may Allah have mercy on him, I am met with waves of unrelenting nostalgia and melancholic yearning for a place and time that, for the most part, I am a stranger to. Slivers of time spent in a home away from home have left me with everlasting memories that shadow the moments that made them. The sound of my grandmother reciting Quran after praying Fajr. The chant of hundreds of children reciting their daily lesson from a wooden tablet clutched in their laps.

When I have the privilege of being present when the elders make dhikr together, I am transported to the same place. A young xirrow quietly memorising a poem in the corner of the masjid. A distant rattle of a koor placed on a camel’s neck, her cry reminiscent of the jibaad olol Careys Isse choruses in his poem Maxaaa Ani Igu Jira. This is no coincidence.

It is no coincidence that this style of recitation—most common in Sudan, Somalia, and the wider Horn of Africa—draws comparisons to West African styles such as that of the Soninke peoples, although they differ significantly. The danger of grouping Sub-Saharan African practices is not lost on me, but the underlying commonality that stretches from the Horn through the Sahel all the way to the Gambia is a distinctively African tone.

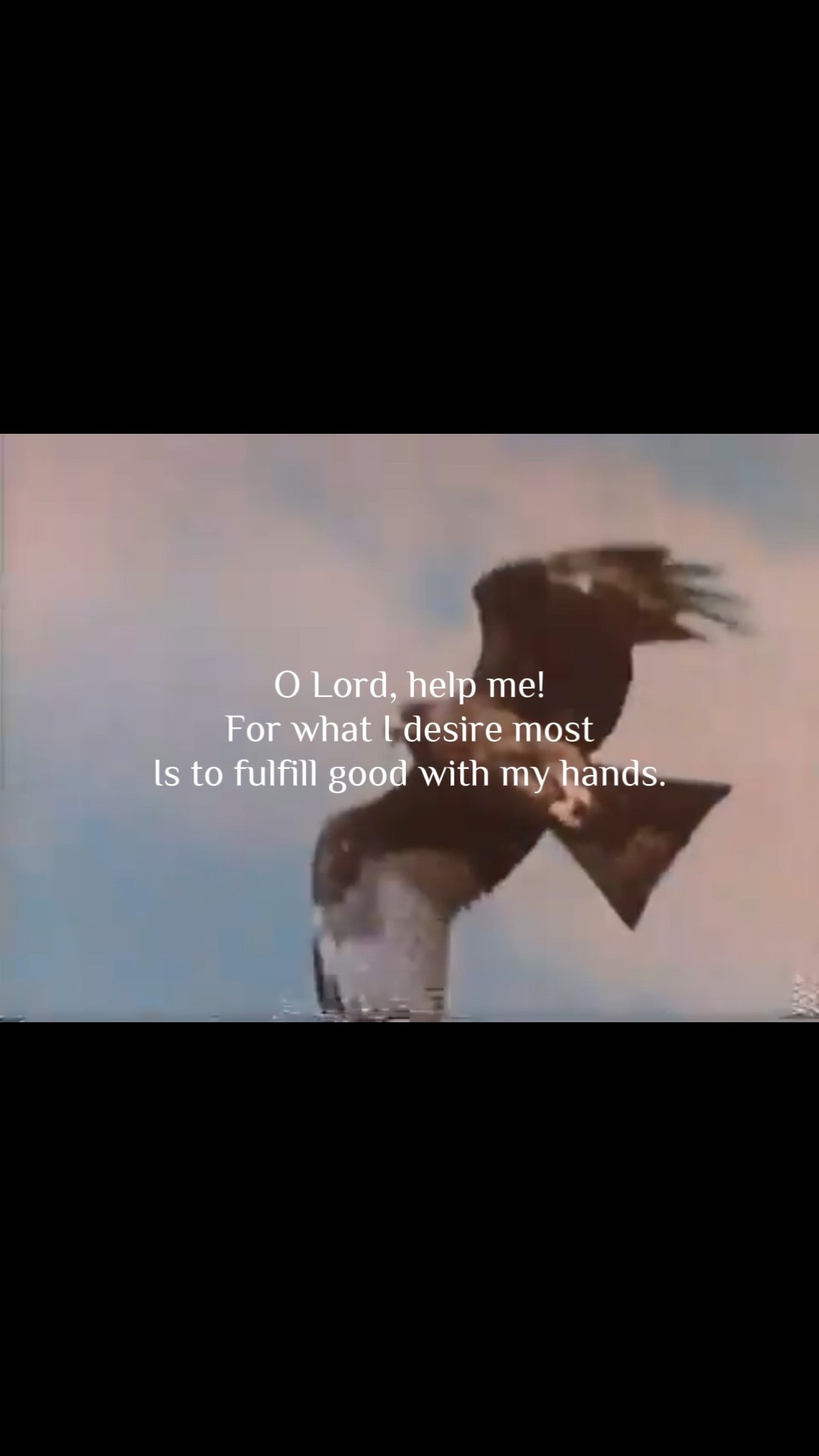

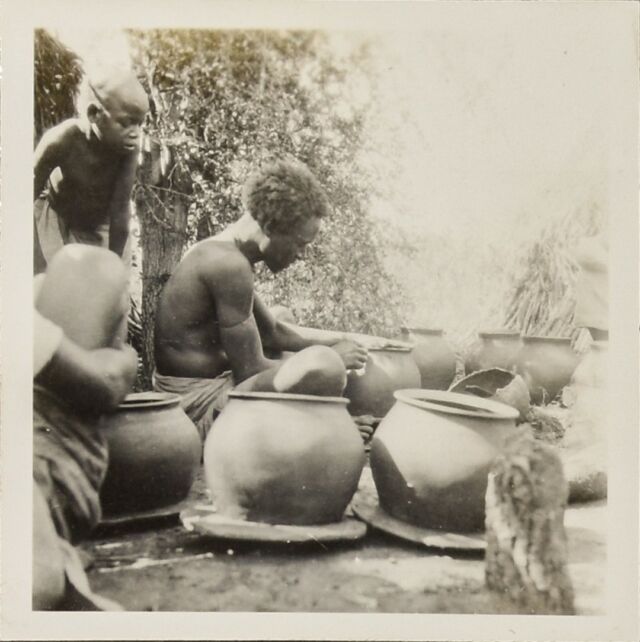

To better understand these tones, it is helpful to first look at the way the Quran is taught and memorised across Africa. There are a plethora of regional names for the same institute: in Sudan, a khalwa; in Somalia, a dugsi; in Senegal and the Gambia, a daara. Across the Muslim world, the most common name is madrasa. Although globally the setting varies, the scene in Africa is soothing in its consistency. A building close to or attached to a mosque, often in rural areas and constructed from humble clay or mud bricks, or possibly even a thatched hut; pots of black ink; wooden tablets with excerpts of the Quran carefully written across them; and the steady, bright hum of children’s voices reciting the Quran.

The process by which students memorise the Qur’an follows an order as old as the tradition itself. A child begins by learning the Arabic alphabet, then moves to copying and reciting short verses under the close supervision of their teacher. Each line written onto the wooden table is recited repeatedly until it becomes second nature. Lessons progress in difficulty until the student can open any page and read fluently. Only then is the student deemed ready to begin the extensive process of memorising the Qur’an.

Under the instruction of the ustādh, the student writes a new portion of the Qur’an on their lawḥ each day, recites it until memorised, and recites it blindly to their ustādh or a senior student, who corrects mistakes, washes the tablet clean, and repeats the process the next day. This cycle of inscription, recitation, and memorisation forms the rhythm of Qur’anic education across much of Africa. Through this orally transmitted programme, regional tones and acoustic cultural patterns infuse themselves into the recitation of the Qur’an.

Khalwa pupils in Mauritania holding wooden tablets.

Throughout their studies, the student learns the words of the Qur’an, the science, and the sound of it: the delicate balance of articulation and melody that defines Qur’anic recitation. The rules that govern these sounds, known collectively as tajwīd, and the recognised forms of recitation, or qirāʾāt, which vary across regions. It is important to note that these fields of Qur’anic science, and the texts they are based on, do not specify or govern any rules regarding tone and pitch.

Tajwīd is the foundation of Qur’anic recitation: a technical discipline concerned with articulation, timing, and the preservation of meaning. Its rules govern how consonants emerge from the mouth (makhārij), the qualities they carry (ṣifāt), the correct handling of elongation (madd), and the discipline of pausing and resuming (waqf wa ibtidā’). Classical manuals such as Ibn al-Jazarī’s al-Muqaddimah al-Jazariyyah1 emphasise a single goal: to read the Qur’an exactly as it was transmitted, letter for letter, without distortion.

Ibn al-Jazarī’s famous maxim is blunt:

“وَلَيْسَ بَيْنَهُ وَبَيْنَ تَرْكِهِ إِلَّا رِيَاضَةُ امْرِئٍ بِفَكِّهِ”

“There is nothing between correct tajwīd and its neglect except a person’s willingness to train his mouth.”

Once tajwīd is established, reciters choose a riwāyah from a particular qirāʾāt. These are recognised methods of recitation; a riwāyah is a specifically narrated transmission of a qirāʾāt. Seven qirāʾāt are widely agreed upon by scholars, with ten recognised more broadly. They govern pronunciation, permissible vowelisations, and small variations. None of these descriptions substitute for hearing them; the video below includes a verse-by-verse reading of the ten qirāʾāt, with differences highlighted.

The riwāyah dominant amongst reciters in Sudan and the Horn of Africa—especially those who recite in this ‘style’—is Al-Duri from the qirāʾāt of Abu Amr al-Basri. Although it was once the most popular in the Mashriq, Ottoman influence saw to the spread of the Hafs riwāyah, now the most commonly used2.

Maqām are melodic modes used by many reciters to colour and beautify recitations of the Qur’an. A completely aesthetic set of devices, they are permitted by many scholars so long as tajwīd is observed, but it’s important to note: they are not a religious obligation, and reciters typically fall into melodic patterns naturally, not through a learned scale or through ‘singing’ the Qur’an. A reciter will often shift maqām depending on the subject matter of the verses they recite, shifting tone to reflect or convey emotions felt through the recitation. The video below covers some of the most well-known maqām and the emotional context in which they’re often deployed.

The reciters whose ‘style’ forms the crux of this essay lean towards pentatonic melodic gestures, intervals and formulae that resemble regional singing and poetic traditions. This produces the soulful quality that we all identify. Listen below to a recitation of Surah Al-Duha by a Somali qari in a traditional tone, then compare the breathwork, pitch, and cadences to the excerpt of a poem recited by the late Abdullahi Suldaan Timacade.

The first clip below is an excerpt of a dobeit poem by the late Mahmood Wad Al-Khawyia. The second is of Sheikh Al-Zain Muhammad Ahmad—one of Sudan’s most beloved reciters and a personal favourite of mine—who articulates the presence of local sonic culture in Qur’anic recitation:

“This is the tone of the environment I grew up in—the desert. It sounds like dobeit. The reciters in the Levant recite according to the melodies they know, as do the ones in Egypt, the Hijaz, North Africa, and elsewhere.”3

His words say what pages of explanation cannot. Don’t take my word for it—listen for yourself.

The excerpts below—a Soninke recitation and a Somali subac—come from opposite ends of the continent, yet their sonic resemblance is unmistakable. Both traditions centre on communal recitation circles in which students read verse by verse, with the group often joining together at the end of each āyah. Despite the geographical distance, they share the same tonal palette: a modest pentatonic scale, a steady mid-range register, and ornamentation that is present but deliberately restrained. Pitch is coloured through gentle slides, subtle inflections, and brief held tones rather than wide leaps or dense melisma.

What emerges is a shared cadence—calm, grounded, and text-forward—shaped not by imitation but by parallel educational cultures. The dugsi in the Horn and the daara in Senegal, Mali, and the Gambia foster nearly identical practices: outdoor group recitation, oral imitation of the teacher’s tone, and a rhythmic call-and-response structure that naturally imprints itself on the student’s voice. These environments create an acoustic memory that follows the reciter long after they leave childhood.

I hope the clips below convey the beauty and subtlety of this shared sonic world far better than any description could.

By the late twentieth century, many regional recitation styles—particularly in Somalia—were beginning to buckle under a growing homogenising force: the rise of a globalised Qur’ānic sound centred on Saudi and Hijazi norms. This transformation was neither accidental nor merely a matter of taste. Ethnomusicologist Michael Frishkopf argues the mass distribution of Qur’ān tapes created a “transnational Islamic soundscape” that increasingly standardised what counted as “proper” recitation4. Once cassette tapes and, later, CDs became ubiquitous, the voices that travelled furthest were those of ʿAbd al-Bāsiṭ, al-Minshāwī, and eventually the Saudi imams of the Ḥaramayn.

The widespread circulation of these recordings, combined with the ascent of Salafi movements, accelerated the erosion of older regional tones. In the name of purifying religious practice, critics dismissed African and other non-Arab tonalities as unnecessary ornamentation or uncomfortably close to singing. Yet, as Frishkopf notes, these critiques conveniently ignore that all Qur’ānic recitation is shaped by local sonic culture—including in the Gulf itself.

In his essay The Conception of Islam in Somalia, Dr Abdurahman Abdullahi describes how the rise of Salafism placed Somali graduates of Saudi Islamic universities in the 1970s on a “collision course” with the country’s deeply rooted Sufi traditions5. Returning with an imported hostility towards local practices, they helped reframe long-established forms of devotion—including recitation styles—as deviant or impermissible. The decline of traditional modes of recitation was thus collateral damage in a much broader engineered shift: a deliberate ideological realignment that elevated one regional sound as universal and relegated others to the margins.

Despite all this, homogenisation never completely erased regional sounds – they were maintained in memory, in rural areas, and in recordings. With the introduction of social media and the decentralisation of media, the same technological forces that once aided erasure, began to revive it. Short-form video created a space where obscure local reciters could reach audiences at home and in the diaspora overnight. All of the clips above I found on TikTok.

Social media is unfolding the shadow of the standardisation that its predecessors established. As the pool of sonic aesthetics continues to grow and diversify, so do recitations across the world. A young person learning the Qur’an today can listen to Al-Minshawi to perfect their articulation and listen to Sheikh Noreen to add ornamentation. Elements of both reciters can be woven into the growth and discovery of their own personal voice.

It is important to clarify that this essay is not meant to diminish the value or beauty of other styles of recitation—Al-Minshawi, Maher Al-Mu’aiqly, and other reciters remain among my personal favourites, and their voices continue to inspire Muslims around the world.

Rather, this post is an attempt to articulate the resonance I felt when I first listened to traditional Somali and Sudanese recitations, a soundscape that has long stirred a particular nostalgia and longing within me. In this sense, it is a tribute to the late Sheikh Noreen Mohammed Siddiq, may Allah have mercy on him, whose voice embodied this heritage.

I pray for the people of Sudan during the current conflict and hope for their safety and peace.

اللهم كن لاخواننا المستضعفين في بلاد السودان. اللهم كن لهم عونا ونصيرا وظهيرا

اللهم ارحم موتاهم واشف مرضاهم

اللهم عليك بالظالمين فانهم لا يعجزونك

- https://tajweedindepth.com/Muqaddimat-al-Jazariyyah-english-Detailed.pdf ↩︎

- http://www.ibnamin.com/recitations_current_places.htm ↩︎

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55935509 ↩︎

- https://sites.ualberta.ca/~michaelf/Mediated_Quranic_Recitation_(Frishkopf).pdf ↩︎

- https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1240&context=bildhaan ↩︎