Without the work of Somali archivists and historians on platforms like X, vital elements of our history and culture would face the very real danger of vanishing, quietly erased from collective memory.

Not long ago, while going through some of my father’s papers, I came across a remarkable collection: documents from the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), a nationalist movement that fought to liberate the Somali-inhabited Ogaden region from Ethiopian rule and unite it with Somalia.

WSLF fighters rallying in the liberated town of Qalaafe, 1977.

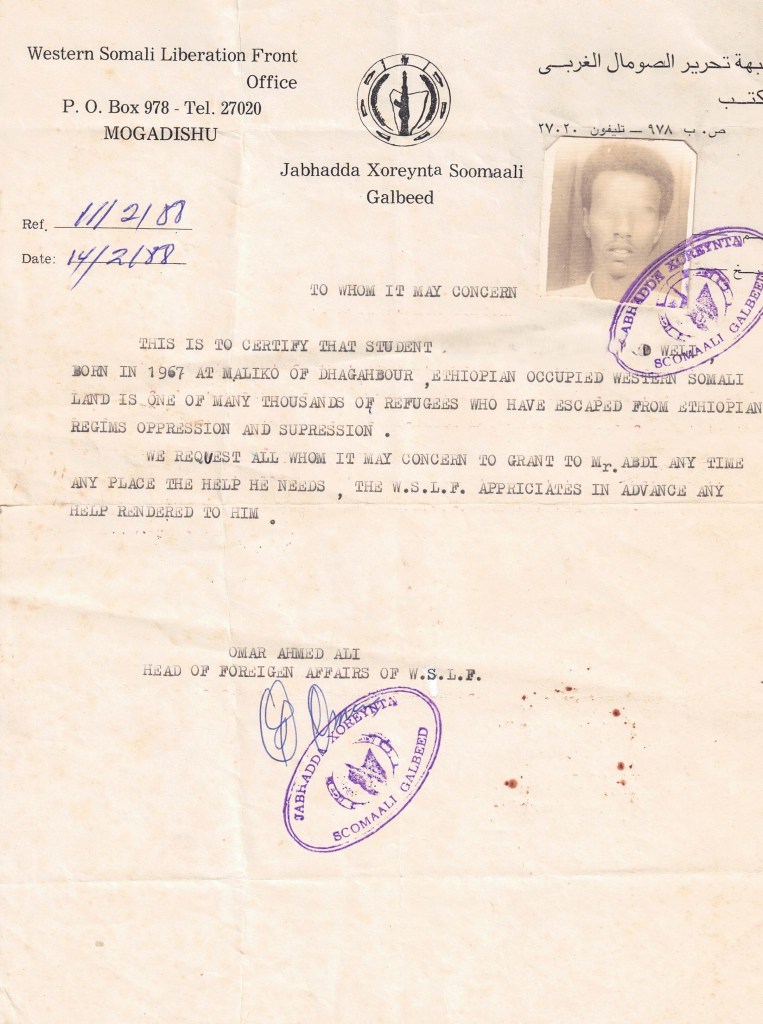

Among them were letters of support issued by the WSLF, recognising the plight of refugees from the Ogaden region and urging readers to support my father as he prepared to study at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. The letters weren’t just rhetorical gestures; they were practical instruments. Because Al-Azhar would not recognise his Ethiopian high school diploma, Ethiopia being a non-Arab state. My father, despite his extensive informal studies in Arabic and Islamic jurisprudence, could not obtain a visa through conventional channels.

The WSLF intervened, reclassifying his academic credentials under Somali authority. This meant he could be accepted into the university without repeating years of schooling. It was an act of solidarity that spared him from being trapped in a bureaucratic loop that would’ve spanned years.

A support letter from the Western Somali Liberation Front, 1988.

When I found those documents, I knew immediately who I wanted to share them with. Not just fellow young Somalis online, but a particular individual. Abdimalik Ali Warsame, a researcher and archivist focused on military history, foreign intervention, and Islamic political movements in the Horn of Africa, and the founder of somalihistoryarchive.com. He’s active on X at @walaalwhoops and is the author of a piercing analysis on Geeska, detailing the longstanding relationship between Ethiopia and the Zionist entity in their efforts to undermine Somali nationalism and obstruct the emergence of a unified, Muslim regional power.

Coming across those WSLF documents was exciting, but storing them on my computer wasn’t enough. They deserved better. They deserved to be shared, studied, remembered. It’s no coincidence that I knew exactly who I wanted to entrust them to, Abdimalik’s work had long resonated with me. I’ve followed his X posts for some time, especially those related to the WSLF and the Ogaden region, a region I call home.

Archivists like Abdimalik are not merely content creators or hobbyist historians. They are custodians of memory. What they’re doing is far more than sharing old clippings — they are constructing a parallel archive. A people’s archive. One that exists outside the reach of governments, beyond the silence of broken institutions and the locked rooms of colonial museums.

Rich nations like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom invest hundreds of millions, sometimes billions, of dollars in preserving everything they deem historically relevant. From Indigenous artefacts to 1970s kitchen appliances, bus tickets, land deeds, family photos, and even cereal boxes .They digitise it all. They build the infrastructure to ensure their cultural memory lives on. These are nations with the capacity to store their history in cold vaults and digital clouds, curated by archivists and funded by state grants.

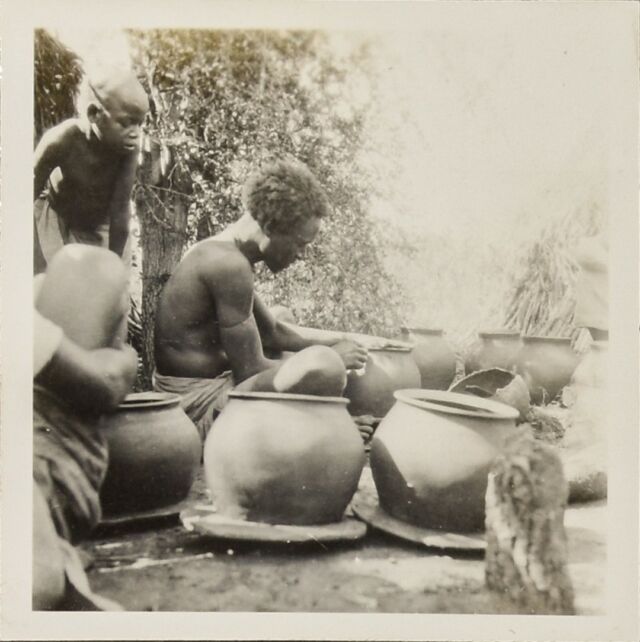

A Somali man making a clay pot in Gelib, 1933, held at the Powell-Cotton Musuem. An example of one of many records held abroad in the museums of former colonial powers.

Somalia, like many nations that have faced war, collapse, and displacement, does not enjoy such luxuries. We do not have a billion-dollar national archive. Decades of war, neglect, and institutional erosion have left vast swathes of our history vulnerable to “falling into oblivion”.

But in that vacuum, decentralised efforts are doing what formal institutions cannot. Somali archivists, historians, translators, and poets are doing the slow, careful work of rebuilding our historical record — connecting timelines, contextualising events, uploading testimonies, linking newspaper clippings to oral histories. They are building a Somali narrative, for Somalis, on our own terms.

It is easy to find, it outlives politics, and most importantly, it is ours.

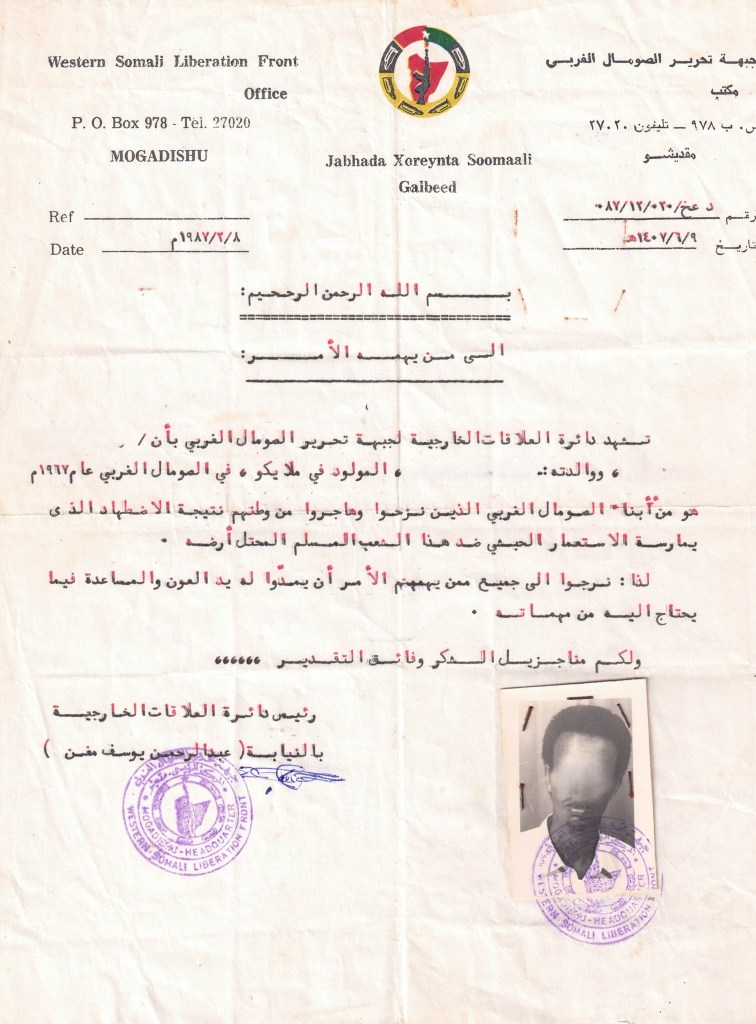

“In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful:

To whom it may concern Mogadishu The Foreign Relations Department of the Western Somali Liberation Front certifies that [] and his mother: [], born in Malayko, Western Somalia in 1967 AD, is one of the sons of Western Somalia who were displaced and emigrated from their homeland as a result of the persecution practiced by the Abyssinian colonialism against this Muslim people whose land was occupied

Therefore: We ask all concerned to extend a helping hand to him in his required tasks. We thank you very much and express our deepest appreciation to you

Head of the Department of Foreign Relations Acting”

A similar support letter, written in Arabic, 1987.

To all Somali archivists, researchers, collectors, poets, translators, and memory-keepers — I offer my deepest respect. Your work is nothing short of essential. You are preserving our dignity, our identity, and our truth.

But I also offer a word of caution: social media is fragile ground. Posts can be shadowbanned, accounts deleted, threads misreported or buried. Algorithms change. Censorship arrives subtly, then suddenly. We have already seen how rapidly platforms like X can shift in tone and policy.

That is why I urge Somali archivists — and all who care about historical memory — to safeguard their work. Do not leave it all in the hands of tech corporations. Mirror your posts. Host your threads, essays, and archives on your own websites. Back up your material to hard drives and independent servers. Share files with trusted peers. Use the platforms, but do not be owned by them.

Great efforts were made by those before us to uphold our culture and history in the face of upheaval, fragmentation, and displacement. It is now our responsibility to preserve, strengthen, and carry it forward, particularly in the digital realm.

We must ensure our future generations inherit a record of who we were — not what others said we were.

A list of my personal favorite archives/archivists:

- Abdimalik Ali Warsame, known on X as @walaalwhoops

- @hornaristocrat

- @thetipofthehorn

- @dhageeyso

- @archiveafrica

Leave a comment